Factors responsible for the inadequacy of enforcement of the laws The factors responsible for the inadequacy of enforcement of the laws on corrupt practices lie in insincerity, partiality, self-interest and downright perversion or subversion on the part of the authorities. Illustrative examples of the prevalence of these factors abound, but only two cases, one involving President Jonathan and the other, President Obasanjo, need be mentioned for present purposes. A complaint was made to the Code of Conduct Bureau (CCB) that Nuhu Ribadu, former Chairman of the EFCC, did not declare his assets as required by the Code of Conduct.

In a categorical statement, the Bureau said that Nuhu Ribadu submitted no assets declarations to it either before or after his tenure in the EFCC. The Bureau’s affirmation of that fact is conclusive of Ribadu’s failure to do so; any assets declaration said to have been found misfiled in the office of the Attorney-General of the Federation is not a proper and valid assets declaration as required by paragraph 3 of the Third Schedule to the Constitution.

The Bureau, after due investigation, referred the matter to the Code of Conduct Tribunal (CCT) for trial, and, while the matter was pending before the Tribunal, it was withdrawn on the direction of the President, and Nuhu Ribadu freed from the charge of contravention of the Code. The withdrawal is an assault on the Code as a device for checking and possibly eradicating corrupt practices. What makes it even more condemnable was the illegal process by which the withdrawal was effected.

It was effected by the Attorney-General entering a nolle discontinuing the proceedings before the CCT in purported exercise of the power given to him by section 174(1) of the Constitution “to discontinue at any stage before judgment is delivered any …… criminal proceedings against any person before any court of law in Nigeria”.

The constitutional propriety of the withdrawal of the case based on section 174(1) raises two issues. First, is the CCT a court of law within the meaning of section 174? Second, is failure to declare assets or “to observe and conform to” the other requirements of the Code of Conduct a criminal offence under the Constitution, so as to make proceedings in a case in the CCT for such failure, criminal proceedings in terms of section 174? If the answer to either or both of these two questions is in the negative, then, section 174 is clearly inapplicable, and the withdrawal of the case against Ribadu is null and void.

The answer to the two questions is provided by the CCT itself in a case for corruption brought before it by the Federal Government (FG) under former President Obasanjo against Dr Orji Uzor Kalu, former Governor of Abia State, and in which the Governor raised as a defence, his immunity under section 308(1) of the Constitution. The CCT, speaking through its then Chairman, Justice Constance Momoh, held the immunity inapplicable as a defence to the suit, on the ground that the Tribunal (i.e. the CCT) is not a court, but a purely disciplinary body, that it has no power to try criminal offences, and that proceedings before it are sui generis and are not civil or criminal proceedings, see Federal Republic of Nigeria v. Dr Orji Uzor Kalu, Charge No. CCT/NC/ABJ/KW/03/3/05/MI (decision delivered on 26 April, 2006).

The Federal High Court had earlier in 2004 come to the same decision in an application to it by Governor Joshua Dariye of Plateau State for an order to restrain the CCT which, at the instance of the FG of President Obasanjo, had issued a warrant for the arrest and detention of the Governor for failure to declare his assets and for corruption brought against him by the FG.

In granting the restraining order against the CCT, the Federal High Court, per Justice Jonah Adah, held that the CCT, as conceived by the Constitution, is not a court of law invested with power to try criminal offences and to impose criminal punishments following upon conviction, but only a disciplinary body; that the “punishments” it is empowered to impose by paragraph 18 of the Fifth Schedule to the Constitution, are intended, not as punishments for a criminal offence in the strict legal sense of the term “punishment”, but as disciplinary sanctions designed, not really to punish, but to discipline and “keep public life clean for the public good” : see Federal Republic of Nigeria v. Chief Joshua Chibi Dariye.

Apart altogether from these two specific decisions noted above, the term “court of law in Nigeria” has a distinctive meaning under the Nigerian Constitution as referring only to courts in which judicial power is vested under section 6(1) & (2) of the Constitution and as listed in section 6(5), namely the Supreme Court; the Court of Appeal; the Federal High Court; the High Court of the Federal Capital Territory, Abuja; a High Court of a State; the Sharia Court of Appeal of the Federal Capital Territory, Abuja; a Sharia Court of Appeal of a State; the Customary Court of Appeal of the Federal Capital Territory, Abuja; a Customary Court of Appeal of a State; such other courts as may be authorised by law to exercise jurisdiction on matters with respect to which the National Assembly or a State House of Assembly may make laws. As the CCT is not included in this list, it is not “a court of law in Nigeria” within the meaning of section 174(1) of the Constitution.

It is not clear why the Federal Government went to the extent of compromising itself by resorting to perversion of constitutional power or an illegality in order to save Nuhu Ribadu from the consequences of his contravention of the Code of Conduct. Insincerity, partiality, self-interest and subversion on the part of Obasanjo in the enforcement of the anti-corruption laws is attested by the fact that he made himself a power above those laws, which could not therefore be enforced against him.

In other words, he arrogated to himself a more or less perpetual exemption from the operation or application of the laws. It is this more or less permanent condition of untouchability that needs now to be removed by the new APC Government under President Buhari. The re-invigorated fight should give no quarters to a sacred cow, neither Jonathan nor Obasanjo nor even Buhari himself.

Being subject to the President’s control and direction and being also mere tools in the service of his regime of personal and autocratic rule, the Code of Conduct Bureau, (CCB), the Code of Conduct Tribunal (CCT), the Independent Corrupt Practices Commission (ICPC) and the Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC) were totally impotent to apply the anti-corruption/abuse of office laws and their sanctions against him; they were impotent even to investigate him, which is really the only sanction enforceable in actual practice against an incumbent President.

In a telling confession, the then chairman of the EFCC, Nuhu Ribadu, was reported in the Vanguard newspaper of 30 January, 2007 to have said: “If I don’t do what the President asked me to do, he is going to fire me and I don’t want to be fired.” That says it all. After filing in the Federal High Court on 23 May, 2005, his suit against President Obasanjo in respect of the presidential library project, Chief Gani Fawehinmi on 6 June, 16 June and 20 June, 2005 respectively petitioned the CCB, the ICPC and EFCC on the matter.

All three agencies duly acknowledged receipt and promised to investigate the complaint, but no action appeared to have taken on the petition in any of the agencies. It shows insincerity on the part of EFCC that it was dragging its feet on the investigation or that the investigation, if any, was not being pursued with the same vigour and zeal as its investigation of allegations against Governors Dariye, Alamieyeseigha, Fayose and others.

The public expects to be informed of, indeed under a government where transparency is practiced, they are entitled to know, the outcome, if any, of the investigation or, if they were still going on, why it was taking so long to complete them. Immunity has nothing to do with this. For, as the Supreme Court has held, the immunity of an incumbent President or Governor under section 308 does not protect him from investigations by the police, the CCB, the ICPC and the EFCC nor does it relieve the Bureau of the duty cast on it by the Constitution to refer, after its investigation, Gani Fawehinmi’s complaint to the CCT.

The failure or neglect of the ICPC to investigate Chief Gani Fawehinmi’s complaint is not excused by the explanation given by its new chairman, Hon Justice Ayoola, a highly respected retired justice of the Supreme Court, that, since his assumption of office in the latter part of 2005, the Commission had received no complaints against President Obasanjo. Surely, his duty or that of the Commission to investigate and take follow-up action is not limited to complaints received after his assumption of office. Or was he suggesting that the complaints against the 26 State Governors investigated by his Commission were all received since his assumption of office?

According to a recent announcement, the Commission, (i.e. the ICPC), having completed its investigation, had requested the Chief Justice of Nigeria to appoint a Special Counsel to conduct interrogation of the 26 State Governors under section 26 of the ICPC Act. The announcement stated that President Obasanjo had approved the action of the Commission in this regard. In any case, the explanation that no complaints against President Obasanjo had been received by the Commission since Justice Ayoola’s assumption of office as chairman, should surprise no one, and it proved nothing. People are either scared to come forward and make complaints or simply consider it futile to do so, knowing that nothing will ever come out of it.

THE Courts, on their part, are precluded from entertaining any suit against the President while in office because of the immunity conferred on him by section 308 of the Constitution. It might have been thought that he would not want to avail himself of the benefit of the immunity in view of his public posturing as a vehement detester of the immunity, but he did plead it in the suit filed against him in the Federal High Court, Abuja by Chief Gani Fawehinmi in connection with the Olusegun Obasanjo Presidential Library project: see Chief Gani Fawehinmi v. President of the Federal Republic of Nigeria (General Olusegun Obasanjo) & Ors, Suit No. FHC/ABJ/CS/287/2005.

If he sincerely detested the immunity, as he had given the public to believe, then, he should have had the courage of his conviction and reject the benefit of its protection for himself. It is another mark of his insincerity that he should have pleaded the immunity in the library project suit.

As expected, the Court, in a Ruling delivered on 12 October 2006, upheld the President’s immunity and dismissed the suit. It is not only insincere but it also smacks of a false show of virtue that the same President who arraigned Vice-President Abubakar and some State Governors on corruption charges before the CCT and/or before the courts in violation of their constitutional immunity should unashamedly get the Federal High Court to dismiss on the ground of the very same immunity, the suit brought against him for corrupt practice and abuse of office.

The impotence of the CCB, the CCT, the ICPC and he EFCC to take action in the form of investigation against the President left the National Assembly as the only body with the independence and capacity to do so, but unfortunately the Assembly too had been sucked into the vortex of President Obasanjo’s personal rule machine or how else could the ICPC and EFCC Acts have passed through the two legislative houses with their obnoxiously unconstitutional provisions? The National Assembly’s moves to impeach him have come to naught more than once. Happily, the Assembly, by its action in the tenure elongation saga, seemed to have regained part of its capacity for independent action.

The Senate’s investigation into the affairs of the Petroleum Technology Development Fund (PTDF) might well set the stage for the enforcement by the National Assembly of the sanction of impeachment reposed in its hand by the Constitution. But the Senate investigation was, regrettably, limited to PTDF money and did not embrace the Marine Float Account and lodgments into the Moffas Account from other sources besides PTDF or indeed other areas of public expenditure. Even the Senate’s PTDF investigation ended at long last due, to corrupt manipulation, in a disgraceful exoneration of Obasanjo.

Concluding remarks The fact that an incumbent President is, as a practical matter, free from the sanctions of the fight against corruption/abuse of office is the reason why it has made and can make hardly any appreciable and lasting impact on the incidence of corruption in the country. If the object of the fight is, in the words of section 15(5) of the Constitution, to “abolish all corrupt practices and abuse of power” (emphasis supplied), and not just to punish certain individuals guilty of them, then, the President, as the leader of the nation, must be seen to be a sincere, untainted crusader against corruption/abuse of office.

Corruption has become a way of life in the country, and what is needed to abolish it is to create faith in the fight among the people, which cannot be done unless the President, as leader of the nation, is perceived to be corruption-free. Without this, no amount of campaign slogans or punitive action against individuals, especially when such action is selective, as Obasanjo’s war certainly was, will make people give up decades-old attitudes and practices.

The President must lead the campaign by example, not by seductive slogans alone, which, unless matched by public perception of him as corruption-free, will simply undermine, if not completely destroy, faith in the fight. The generation of faith in the fight among the people is therefore a sine qua non in the eradication of corruption. The President must inject into the fight a truly crusading spirit transparent enough to inspire faith and to carry everyone along.

The truth of this is borne out by General Murtala Mohammed’s anti-corruption crusade in 1976 as Head of the Federal Military Government (FMG). He launched the crusade by first surrendering to the state his assets acquired by the wrongful use of his office. By this singular and unprecedented act, by his revolutionary ardour to clean up the society of the cankerworm of corruption and by his sheer zeal and fervor characteristic of one waging a religious war, he was able to create faith in the crusade among the various sectors and levels of the Nigerian society. People were simply propelled to take a cue from him and join the bandwagon of the crusade.

Within just six months the mighty edifice of corruption began to crumble. But, alas, he and his awe-inspiring anti-corruption efforts were silenced by the assassin’s bullet. With General Mohammed’s demise, the eradication of corruption was also eclipsed, not for want of anti-corruption measures, but mainly because the successive rulers, both military and civilian, were not prepared to make example of themselves as corruption-free leaders, as General Mohammed had done. The General Obasanjo administration that took over from him did not invoke Mohammed’s draconian Corrupt Practices Decree 1975 or the Public Officers (Special Provisions) Decree 1976 against any of the member of the administration. While it dealt severely with corruption committed during the Gowon administration (other than corruption that might have been committed by its own members during that administration), corruption by its members was left undisturbed and so continued unabated.

Since the 1976-79 Obasanjo administration and the public service under it were not probed by the succeeding civilian administration, the extent of corruption during its rule has not been publicly exposed, but its prevalence cannot and has never been doubted. And if corruption continued in the face of enforcement actions under the stiff corrective measures, it might have been expected to flourish, as it in fact did, when the corrective force was removed in October 1979 on the return to civilian rule.

The Buhari Military Government 1984–1985 had again busied itself with the investigation and punishment of corruption committed under the ousted civilian government of the Second Republic and the recovery of assets corruptly acquired by the members or officials of that government. The investigations into past corruption and its punishment by long prison sentences and forfeiture of assets corruptly acquired did instill fear into the minds of many public servants, yet, it seems clear that no real impact had been made on the incidence of corruption. In its preoccupation with the past, the administration did pretty little, if anything, to enforce its stiff, punitive anti-corruption legislation against its own members or against current corrupt practices which were thus again allowed to continue unpunished and unredressed, unless a succeeding government should in future decide to focus the searchlight on them. And so the rot has continued up till now, eating deeper and deeper as we gravitate from one bungling government to another.

President Obasanjo claims in his characteristically propagandist fashion that his war against corruption is one of the most successful in the world, citing the cases of the former Inspector-General of Police, Governors, Senate President, ministers and others removed from office upon an indictment for corruption. But the success of his war is no more than the kind of success achieved by the anti-corruption measures of General Buhari’s Federal Military Government between 1984 and 1985, a success measured by long prison terms and forfeiture of assets imposed on those found guilty of corruption by special military tribunals, with prison terms ranging from life to 25 years, 23 years to 21 years, though later reduced by the Supreme Military or the Armed Forces Ruling Council. However, the long prison terms and forfeiture of assets of the culprits left no lasting impact on the problem of corruption simply because people had no faith in the sincerity of the measures.

All what is said above cannot but create a credibility gap between the government and the public. A government that enacted anti-corruption measures but refused or neglected to enforce them against the ruler himself cannot but appear to its citizens as insincere and unworthy of credibility and trust. The lack of faith in President Obasanjo’s anti-corruption war amongst the generality of Nigerians is, as earlier stated, the major problem militating against the effectiveness of the so-called war. It is not enough, therefore, in creating an ethic of public probity, that corruption by individuals is being punished if corruption by the ruler himself is not also being exposed and punished. Only if the ruler himself is seen to be corruption-free can public probity become part of the legacy he will be handing over to future generation of leaders.

Obasanjo is only deluding himself in thinking that people are going to give up corruption if he retired from office in May 2007 while keeping the enormous wealth which he has acquired through the wrongful or corrupt use of his office as President, or if numerous others who corruptly acquired billions or millions of naira are allowed to keep and enjoy their ill-gotten wealth while the suffering majority of the population continue to live below poverty line. Having replaced the evil rule of the PDP, the new ruling party, the APC, under President Buhari, must spearhead the desired change, the Social and Ethical Revolution. They should not fail the nation. CONCLUDED

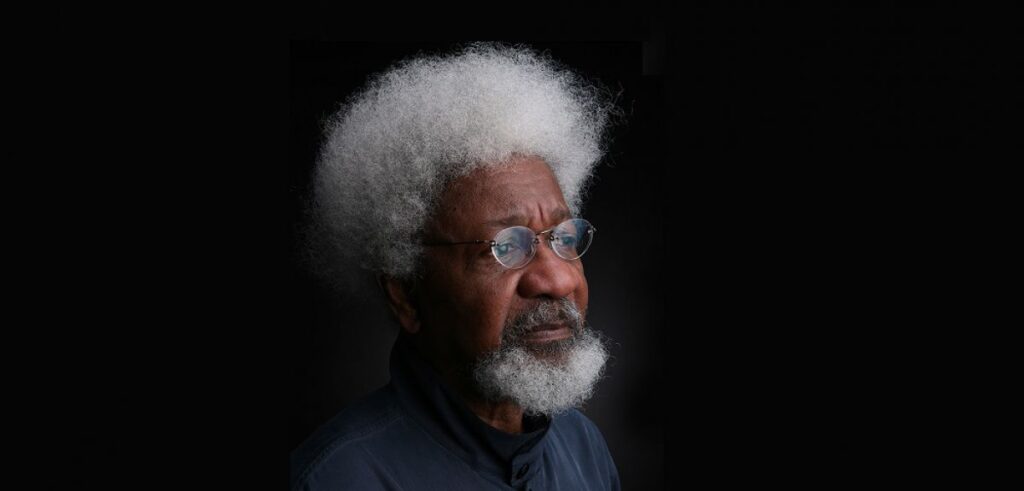

• Prof. Nwabueze, a constitutional lawyer wrote this on behalf Igbo Leaders of Thought