J. P. Singh, a professor of political economy, public policy, and cultural studies at George Mason University (USA), once noted that, in addressing the complex deficits in basic human needs, the cultural sector is usually a primary casualty in policy-making and funds allocation in developing countries. That is why some of us were apprehensive about the implementation of the recommendations of the 2012 reports on restructuring and rationalization of Federal government parastatals, agencies, and Commissions (Oronsaye Panel Report). While previous governments have been reluctant to implement the Committee’s recommendations, including that of President Goodluck Jonathan, who constituted the Committee, President Bola Tinubu has decided to implement elements of the report, to reduce the cost of governance in the prevailing economic hardship. Thus, the National Commission for Museums and Monuments would merge with the National Gallery of Arts, and the National Theatre would be amalgamated with the National Troupe of Nigeria. Similarly, the Nigerian Film and Video Censors Board is to become a department in the Ministry of Arts, Culture, and Creative Economy. While these restructurings, after all, would appear as steps in the right direction, the problems of the cultural sector in Nigeria, which is far beyond mere re-organisation of agencies include poor funding, inadequate or even non-existent infrastructure, and apathetic cultural leadership, all of which are rooted in the lack of a supportive and functional legislative framework. The marginalization of the culture and creative sector in Nigeria, as in most developing countries is usually due to the ambiguity in the value and contributions of the creative and cultural industries, in environments where most people, including political leaders, lack what Pierre Bourdieu termed as cultural capital.

The term ‘creative economy’ was propagated in 2001 by John Howkins in his book, “The Creative Economy: How People Make Money from Ideas.” The sector positions itself at the intersection of economics (contributing to GDP), innovation (fostering growth and competition in traditional activities), social value (stimulating knowledge and talent), and sustainability (relying on the unlimited input of creativity and intellectual capital). It is not by chance or coincidence that the countries regarded as developed (or first world) are mostly those with functional and sustainable cultural and creative industries. Rather, they deliberately prioritise the culture and creative economy in policymaking to harness their capacity to produce jobs and growth, stimulate innovation, drive tourism, and promote culture and identity. These countries, including the United States, Canada, and Western European countries (UK, Germany, France, etc), also engage in cultural diplomacy to accumulate “soft power” for economic and political strength in the dynamics of international power relationships. The British Council, Goethe Institute, and Alliance française are some of the agencies of cultural diplomacy for these countries. With a strategic fostering of the cultural and creative industries (CCIs) through a cultural policy shift from a government-driven (direct public control) to a marketization (market-oriented) model, China, which classifies itself as a “developing” country has also become a major player in the global creative and cultural industries, surpassing most developed countries in cultural infrastructure and international engagements. The economic value of culture in China has come to be seen as an important mechanism of growth for national development. The creative industries provide the information that shapes democratic governance, the designs that shape our physical environments/cities, and the contents and performances that enrich our lives and boost our global image. These industries have proven to be an essential positive energy for societies, bringing joy, and inspiration, and creating opportunities for the people. The creative industries also form the national conversation through which we define our individual and shared values. While the value of the creative industries stretches beyond the economy, as a few of the socio-political (intrinsic) values outlined above indicate, the justification or advocacy for attention to the sector has always required the explication of its contributions to the economy.

In ‘Cultural Times,’ the first global analysis of the cultural and creative industries and markets, published in December 2015, the CCI was identified as a major driver of the economies of both developed and developing countries. Culture and creativity are described as catalysts for development as about 30 million people across the world make a living out of them, generating total revenues of US$2,250b. The study also assesses the economic and social contribution of 11 key sectors of the cultural and creative industries at the global level (visual arts, architecture, books, music, cinema, performing arts, newspapers/magazines, radio, television, video games, advertising) in Asia-Pacific, Europe, North America, Latin America, Africa and the Middle East. The study shows that the contribution of the cultural and creative sectors to the global economy is major. They generate higher revenues than telecommunications services globally (US$1.57 trillion) and employ more people than the automotive industry in Europe, Japan, and the United States combined (US$29.5 million versus US$25 million). In Europe for instance, the CCI sector was found to have employed more people aged 15-29 years than any other sector. The research also shows how CCI plays a decisive role in the economic development of both mature and emerging economies, and they are also a significant driver of urban development. According to Prof. Joseph Nye, former Dean of Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government, “soft power,” which lies in the ability of a country to attract others economically and by extension politically, develops from the fascination of a country’s culture. The United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO) after a panel discussion under the theme “Development Policy and Creative Industries” held on 27 August 2012 also reported that the cultural and creative industries are potent avenues for youth employment.

According to the 2015 report, Asia-Pacific, with the largest consumer base, is the world’s biggest CCI market, generating US$743b of revenues (33% of global CCI sales) and 12.7 million jobs (43% of CCI jobs worldwide). Europe is the second-largest CCI market, accounting for US$709b of revenues (32% of the global total) and 7.7 million jobs (26% of all CCI jobs). Rooted in its history, Europe’s cultural economy enjoys a unique concentration of heritage and arts institutions. Europe also remains a trendsetter on the global stage. The UK, for instance, is a leader in the art market, especially due to its contemporary art. Seven of the 10 most visited museums in the world are European and 30 of the 69 UNESCO “Creative Cities” are also European. A French company, Publicis is a key player in the global advertising industry. In maintaining a leading position in the CCI sector, the European cultural economy relies on a well-structured ecosystem, established on supportive legislative frameworks. North America is the third-largest CCI market with revenues of US$620b (28% of global revenues) and 4.7 million jobs (16% of total jobs).

The Latin American CCI economy generates US$124b in revenues (6% of the CCI global market) and 1.9 million jobs (7% of total CCI jobs). Like Nigeria, countries in the Latin America and Caribbean region are rich in cultural heritage, which forms the basis for the CCI. Africa and the Middle East produce US$58 billion in revenues (3% of the total) and 2.4 million jobs (8% of total CCI jobs). African music has been central to the development of popular music in North and South America and even Europe. Today, African societies including Nigeria, contain cultural riches on which citizens are increasingly leveraging the opportunities offered by new technologies and commercial markets. Film production and viewing supported by digital technologies are now driving employment growth in the CCI, with striking successes. Nollywood, the Nigerian film industry, is now reckoned to directly employ 300,000 people, even when the market is poorly structured and cultural goods, according to Professor Jade Miller of Wilfrid Laurier University (Canada), are largely provided through the informal economy.

Nigeria has not been able to optimise the social and economic benefits of its rich cultural heritage and enormous population of highly creative youths due to inadequate and unstructured funding, lack of necessary infrastructure, and apathetic cultural and creative sector leadership. The need for funds and the optimization of human creativity was highlighted by Giorgio Vasari in his classic work of 1966 “The Lives of the Artists.” According to him, the rebirth in art and culture usually termed the Renaissance, which began in Italy and spread to the rest of Europe in the 14th and 15th centuries is attributable to the money acquired by the Medici family from Banking and commerce. An important driver of innovation and success in the field of cultural production is the availability of funds, which Pierre Bourdieu, a leading French sociologist called economic capital. For high art, with its restricted audience, this funding usually takes the form of sponsorship/patronage, while popular art thrives on the availability of and the ability to reach the greatest markets. In any case, the role of government is essential, either as a direct or indirect player, in driving the production, national/international distribution, and consumption of cultural products.

Funding Inadequacy

Funding has been a perennial obstacle for the cultural and creative industries in Nigeria, which has become a constraint for the experimentation that usually triggers innovation. Consequently, Nigeria’s cultural products have not been able to put up robust international engagements which has become the arena of value creation since the collapse of the Berlin Wall in 1989, which has entrenched a neoliberal order in the global field of cultural production. Due to the lack of attention and funding from the government, support for the cultural and creative industries in Nigeria has followed two major streams. The first was the foreign missions such as the British Council, Goethe Institute, and Alliance française, etc which was driven by cultural diplomacy. The second line of support for the creative industries in Nigeria has been the private entities, usually for corporate social responsibilities and brand engagements by banks, oil, and other multinational companies. For example, in addition to having a rich collection of contemporary art of Nigerians, which is displayed in its branches all over Nigeria, the Guaranty Trust Bank has been a major pillar of the art in Nigeria. In 2011, a partnership between GTBank and Tate Modern London was established to bring governance and legality through the interaction of African-based and international cultural institutions and individuals. The partnership includes the creation of a dedicated curatorial post at Tate Modern to focus on African art, and an Acquisition Fund to enable the prestigious Museum to enhance its holdings of work by African artists. This fund provides GTBank and Tate with an unprecedented opportunity to develop a new framework for collecting, displaying, and interpreting African art within the international arena, where value is constructed. In 2016, Guaranty Trust Bank launched the Art635 Gallery, which is an online art gallery that gives indigenous artists a free digital space to showcase and sell their artwork. Guaranty Trust Bank Plc was also a major supporter of the first exhibit by a black artist on the world-famous Fourth Plinth, Trafalgar Square in London. This reinforces the bank’s position as a foremost African international financial institution. The work, ‘Nelson’s Ship in a Bottle,’ unveiled in 2010, was created by leading British-born, Nigerian Artist, Yinka Shonibare MBE.

Turner Prize-winning artist Yinka Shonibare with his work ‘Nelson’s Ship in a Bottle’ Credit – Matt Dunham/Associated Press

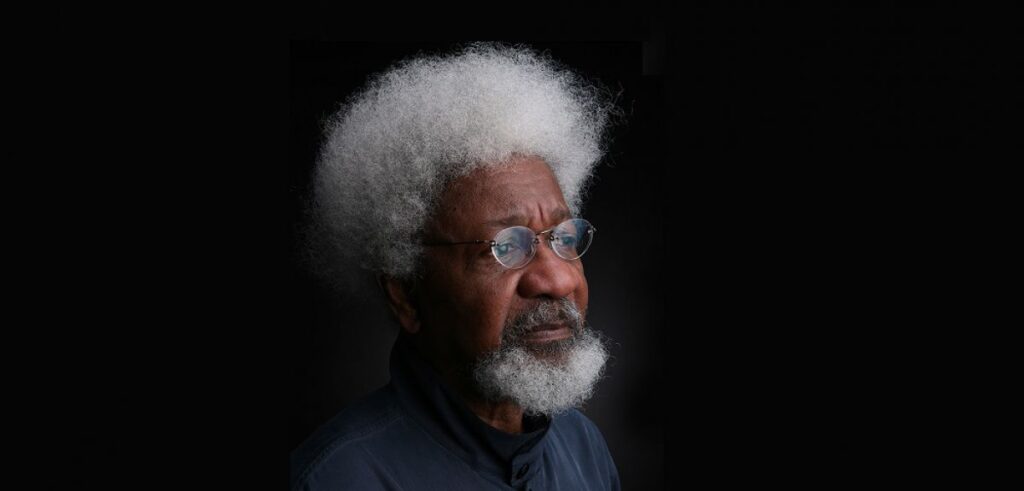

Herbert Wigwe, Former CEO of Access Bank. Photograph: Andrew Esiebo/Getty Images for Global Citizen

As part of its corporate social responsibility, Access Bank has also demonstrated a commitment to supporting the Creative Arts Industry in Nigeria. Tokini Peterside-Schwebig, the Founder of ART X Collective, confirms that in the vision to showcase the depth and diversity of contemporary African art to the world, Access Bank has supported the critical need to nurture and guide emerging talent on the continent through the awards of $10,000 grants to Art X Prize winners. Such awards do not only consecrate creatives in their countries, but they also engender international visibility that strengthens global reputation and valorisation. While the funding from private institutions is highly commendable, they are not sufficient to create the local conditions that are necessary for robust international participation, which has become necessary in the increasingly globalizing world.

Infrastructure deficit

World-class cultural infrastructure is not just a catalyst for urban development, but more importantly, it provides the mechanism for local validation and audience engagement, which is fundamental to robust international participation and valorisation. For example, building a museum often offers opportunities for cultivating domestic audiences for art and developing a new “city brand” that boosts its attractiveness for tourists, talents, investors, and highly skilled workers. Bilbao, Spain’s Basque Country, is now an icon of culture-led urban regeneration. The construction of the Guggenheim Museum led to more than 1,000 full-time jobs, and tourist visits have since multiplied eight-fold. Usually referred to as the “City of the Guggenheim”, because the Spanish official tourism website confirms that Bilbao has changed since the museum was built in 1997, when it has been making an impact due to its groundbreaking structures that serve as an international reference point for modernity, and created by prestigious architects. Cultural infrastructure makes cities more liveable, providing the hubs and many of the activities around which citizens develop, network, and build friendships, build a local identity, and find fulfillment. Paris is one of the French cities designated the European Capital of Culture, which has made it possible to develop cultural projects that contribute to tourist and economic attractiveness. Unfortunately, Nigeria is deficient in terms of the infrastructure required to maximize the potential of the creative and cultural sectors, thereby deprived of all the associated socio-economic benefits needed to attract and justify greater private and public attention.

In Singapore, the development of the visual arts was considered as a way of making the country one of the hub cities of the world. Therefore, deliberate infrastructural developments such as the creation of the National Arts Council (NAC) and National Heritage Board (NHB) facilitated the establishment of museums such as the Asian Civilisations Museum, Singapore Art Museum, and the National Gallery Singapore. Over $500 million was expended on the redevelopment of the old Supreme Court building and City Hall into a befitting gallery with a floor area of 64000 square meters. The National Gallery of Singapore, which opened on November 24, 2015, manages the most extensive public collection of Singaporean and Southeast Asian art, consisting of over 8,000 modern and contemporary artworks. Conversely, the National Gallery of Art (NGA) was established in 1988 with the mandate to collect, preserve, exhibit, and foster a greater understanding of the contemporary art of Nigerians. These make it necessary for the agency to acquire a physical structure exclusively dedicated to the purposes, but the National Gallery still lacks such a physical edifice. This, and the lack of contemporary art museums in Nigeria, deprives artists of the local presentation and validation that is fundamental to sustainable international engagements.

Apathetic leadership

In highlighting how the government’s action in the culture agencies impeded the Nigerian creative industry’s growth, Hassan Momoh, in the Guardian Newspapers of December 31, 2017, identified the appointment of inappropriate leadership for the agencies as an overriding problem. This, he describes as putting “round pegs in square holes.” According to him, leadership ineffectiveness affects Nigeria’s cultural sector as a whole and is not peculiar to the Ministry of Culture or any of its agencies. This he noted has manifested in “repeated instances of bureaucratic bungling that inevitably led to a waste of scarce resources and time.” The Centre for Black and African Arts and Civilisation, an agency, that was on the verge of attaining African Union recognition under Professor Tunde Babawale for example, has been inactive since his exit. In its history, the National Gallery of Art was most active during the tenure of Joe Musa as the Director-General of the NGA. Over the years and despite a mandate that covers the development and support for the living arts of Nigerians, the National Council for Arts and Culture has focused narrowly on the promotion of crafts. Investment in and support for high art or driving the international visibility of Nigeria’s cultural production at reputable arenas for value construction such as the Venice Biennale has never attracted the agency’s attention. Nigeria was placed among countries on the blacklist of unserious speculators by the organisers as a result of inadequate funding, national acknowledgment, and support in such a reputable international consecrating event.

Dak’Art Biennale is a foremost cultural event in Africa, which avails African artists rare opportunities for international visibility since it attracts almost the same crowd of global cultural gatekeepers as the Venice Biennale. In a certain year, the organisers of Dak’Art had signified their interest in making Nigerian contemporary art the focus of the event. However, the Minister of Information and Culture who lacks the understanding of what such a rare opportunity represented ignored the gesture. All these underscore the importance and structuring influence of personal dispositions that Pierre Bourdieu emphasised in cultural participation and governance. People are deployed to cultural agencies and institutions in Nigeria mainly based on political considerations and not for their demonstrated interests, training, or experience, which represents the personal dispositions (habitus) and cultural capital that Bourdieu described as critical in cultural leadership. Research has established that the aforementioned shortcomings are mainly attributable to a lack of functional and supportive legislative frameworks.

Purposeful policy

In his book, The Field of Cultural Production: Essays on Art and Literature, Pierre Bourdieu stresses that art and its producers do not exist independently of a complex institutional framework that authorizes, enables, empowers, and legitimizes them. Thus, cultural policy is fundamental to the governance of domestic production systems for robust international engagements and valorisation, especially when the field of culture has become a vital arena of global political power dynamics. Cultural policy is the government’s actions, laws, and programs that regulate, protect, encourage, and support (financially or otherwise), activities related to the arts and creative sectors. In simple terms, they are the plans, rules, and regulations that govern the creation, distribution, and consumption of art and culture in a locality, state, or country. In developing these policies, governments around the world have been guided by four main approaches, namely the facilitator, patron, engineer, and architect models. The facilitator approach is exemplified by the USA, based on its values of individualism and private enterprise. This model, driven by the pursuit of excellence, puts culture in the hands of the private sector through tax concessions and ensures a diversity of funding sources for art and culture. However, this approach was complemented in 1965 with the establishment of an arm’s length (patron) agency, the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA), the independent federal agency that funds, promotes, and strengthens creative capacities by providing Americans with diverse opportunities for arts participation.

In the 10-Year Strategic Plan, 2024-34 of the Arts Council of Northern Ireland, Roisín McDonough, the Chief Executive writes – “artists are not just creators; they are innovators and entrepreneurs who push boundaries, challenge conventions, and shape the world around us. They are the catalysts for change and their work has the power to inspire and transform society. They have an uncanny ability to provoke conversations, bridge divides, and ignite imaginations. In a time when our society needs healing, connection, and fresh perspectives, the role of artists has never been more crucial.” It is this strong belief in the importance of the arts, that inspired the United Kingdom’s robust support for culture through what cultural policy theorists called the patron model. This model operates in the arm’s length approach, through the Arts Council in England, Wales, Scotland, and Northern Ireland, which is a government agency funded by the public, including the National Lottery Funds, but operates as an independent entity, exclusive of bureaucratic government control.

Taking art and culture as a significant element of social welfare, France and the Nordic countries (Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, and Sweden) adopted the architect’s model in their support for art and culture. In this approach, the main channel of funding for art and culture is directly through the Ministry/Department of Culture. The Nordic countries, known for their robust social welfare systems and emphasis on equality, have embraced the idea of art as a public good and have integrated it into their educational systems and government budgets. They share a common approach to art as an essential element of society that contributes to individual well-being and community development. They incorporate art into various aspects of public life, prioritizing accessibility, participation, and support for artists (cultural democratization).

In France, the state participates in the funding of culture through aid, investment, and subsidies, since culture is taken as the wealth of the country, each year, a significant portion of the budget (€17 billion in 2022) is devoted to culture. Since funding under this model is guaranteed, irrespective of the quality and innovativeness of outputs, it has been highlighted that such approaches could result in creative stagnation. The Soviet Union represents the prototype of the Engineer approach to cultural governance, in which art serves the function of state propaganda, making the state take ownership and total control of art and culture. Joseph Stalin, the epitome of Soviet totalitarianism, believed that art should be used to project a positive image of life in the Soviet Union to its inhabitants. Thus, it should be partisan and supportive of the aims of the State and Party and any art that portrayed a negative view of the State or the Party was illegal. This model appears to have lost relevance since the fall of the Berlin Wall.

Konstantin Yuon, 1927, First Appearance of Vladimir Lenin at the Petrosovet Meeting at Smolny on 25 October 1917, Oil on canvas

The State Russian Museum, St Petersburg.

In providing the necessary infrastructure, sustainable support, and capacity to strengthen the creative (cultural) industries in Nigeria and enhance robust international visibility and valorisation of Nigerian cultural production, deliberate action on establishing clear and functional legislative frameworks is sacrosanct. As I highlighted earlier, there has been a considerable level of private support for the creative sector in Nigeria, but this is not sustainable as it has merely depended on the personal dispositions of the individuals at the helm of these institutions. For example, the level of support for the arts by Guaranty Trust Bank reduced drastically since the death of Tayo Aderinokun, who was an avid patron of the arts. Similarly, we hope to see how the demise of Herbert Wigwe will impact the support of Access Bank for the creative sector. As emphasized by JP Singh, the government of Nigeria has enormous responsibilities in addressing the shortages and challenges of the basic human needs in education, security, and health, it should establish a supportive legislative framework to drive sustainable private interventions. Such a framework would create an environment for steady and sustainable interventions from private and corporate institutions. Therefore, Nigeria needs to review and implement the draft cultural policy document, which is currently enmeshed in political bottlenecks. To aggregate the needs of each sector of the industries, such a review should involve various stakeholders, after the government has reconsidered its cultural sector goals to determine the preferred or appropriate approach amongst the various models.

Dr. Jonathan Adeyemi is a sociology of art and cultural policy researcher in the United Kingdom. He holds a Ph.D. in Arts Management and Cultural Policy from Queen’s University Belfast, United Kingdom and he is the author of the book “Contemporary Art from Nigeria in the Global Markets: Trending in the Margins,” published in 2022 by Palgrave Macmillan.