After taking over power through brute force, General Ibrahim Babangida sought to partner with the International Monetary Fund (IMF), and to birth a generational project of financial captivity for Nigeria under the Brent Wood institution. Nigerians were opposed to the financial package from

I had just been elected as the Public Relations Officer of the Students’ Union of the Obafemi Awolowo University, and Great Ife being the headquarters of the students’ movement in Nigeria, we declared total support for the campaign to reject the IMF loan. This would lead to mass protests, boycott of lectures, baricade of the main Ife-Ibadan expressway and eventual closure of the university. The authorities of the university did not take kindly to the protests whereupon a panel of inquiry was constituted to identify those who spearheaded the protests and to recommend appropriate sanctions.

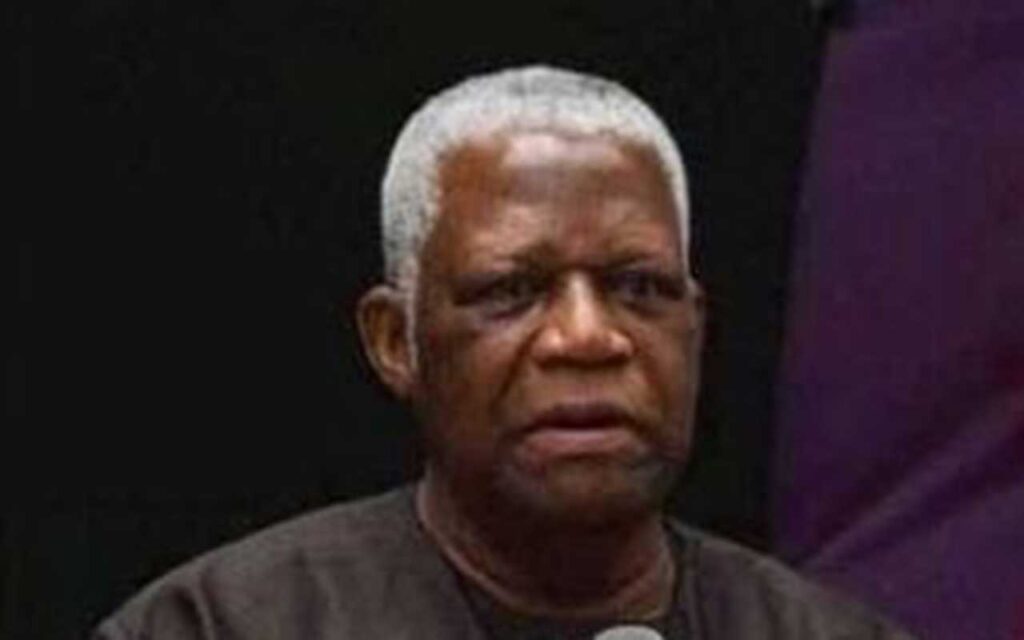

At the end of that exercise, 62 student leaders were expelled from the university, including myself. I had struggled to secure admission to study law in the university after years of sacrifices and support from family and sympathizers so I could not go back home to tell my guardians that I had been expelled from school. My friend, Bamidele Aturu led all the students to the Chambers of Chief Gani Fawehinmi (SAN).

Gani assured us that we would all be reinstated. He assigned lawyers to us who took our briefs, we were fed and then assisted to go back to our various destinations. I went back to Ile-Ife, to partner with fellow students who could accommodate me and provide menial jobs to aid my survival, including as an apprentice in a printing company, assisting transporters, etc. It was a very long period, spanning close to six months.

To hope for anything is to cherish a desire with anticipation; to want something to happen or to be true. It is to have the expectation of obtainment or fulfilment, based on confidence and trust. Towards the period of independence of Nigeria, one of the fears expressed by the minority ethnic groups was the likely dominance of political affairs by the majority ethnic groups, resulting in the setting up of the Henry Willink Commission. Part of the recommendations of that commission was to develop a set of rights for the protection of citizens and to set up vibrant institutions for the resolution of disputes on the basis of equality. The courts then became the focus of all, as a place for the ventilation and settlement of disputes.

The concept of justice through the courts is built upon a set of laws creating rights and responsibilities for all such that in the event of their violation, anyone could approach the court for the enforcement of any of the rights created by law or call to order any person violating such laws. The court is thus referred to as the last hope of the common man because of the right of access granted to all individuals no matter their status. This is best captured in section 6 (1) of the Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria, 1999 where it is stated “the judicial powers of the Federation shall be vested in the courts to which this section relates, being courts established for the Federation.” Judicial power is more specifically defined in section 6 (6) (b) as follows:

“The judicial powers vested in accordance with the foregoing provisions of this section shall extend to all matters between persons, or between government or authority and to any person in Nigeria, and to all actions and proceedings relating thereto, for the determination of any question as to the civil rights and obligations of that person.”

The right of access to the court means that any citizen can sue any person or authority for the enforcement of any right defined by law where there is a violation or threatened violation. Leveraging on this provision and other enabling statutes, Fawehinmi approached the High Court of Justice, Osun State, sitting at Ile-Ife, to challenge the expulsion of the 62 students. He won the case and we were all reinstated. It had to do with the destiny of several students who have today become leaders in various spheres of our national life.

Nobody could have secured such a landmark victory except through the court, which was the very last hope of all the students affected by that draconian act of expulsion. So, please allow me a little time to commend and salute the judiciary in Nigeria, to appreciate all lawyers, civil society organisations, the media and indeed all stakeholders working tirelessly to keep the system of administration of justice alive and afloat in Nigeria.

But for that courageous act by Fawehinmi and the boldness of Hon Justice Ojutalayo, I may not have been able to reach out to you through this piece or even ever realising my dream of becoming an advocate. And the courts have been very courageous in Nigeria, despite the intimidation and harassment from the other arms of government, especially the executive. As a beneficiary of judicial courage, please pardon me when I salute and commend all judges, even in these times.

After one of the several arrests and detentions of Fawehinmii, we filed a case at the Federal High Court, Lagos, to challenge the State Security (Detention of Persons) Decree No.2, which purported to oust the jurisdiction of all courts from questioning anything done under the said Decree. The matter was dismissed by the trial Court, which upheld the provisions of the Decree and thus declined jurisdiction over the case. On appeal, the Court of Appeal, presided over then by the Hon Justice Dahiru Musdapher (later Chief Justice of the Federation), overturned the decision of the High Court and held that Decree 2 was a violation of the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights.

In this same country, Senator Bola Ahmed Tinubu, then Governor of Lagos State, decided to devolve power by creating local council development authorities, leading to a major confrontation between Lagos State and the Federal Government. The matter got to the Supreme Court, which ruled in favour of Lagos State. Time will fail me to mention other occasions when judges have demonstrated uncommon courage to restore law and order and give hope to our people.

Sometime in or about June 2012, I was invited to be a guest speaker by Channels Television on its Saturday programme, Sunrise. Being the last Saturday of the month, I requested for a formal invitation to serve as my pass from the barricade usually mounted by security agencies that were enforcing the programme of environmental sanitation in Lagos State. I left my house in Lekki very early and was able to pass through the roadblocks on the Island but I could not scale through the one mounted at the Ketu end of the Third Mainland Bridge.

Policemen and LASTMA personnel stationed at this junction would have none of my explanations. I called my contact in Channels to speak to them but they would have none of it. They told me point blank that I was under arrest for daring to drive out of my house on environmental sanitation day. I was kept at that point till 10am when the road was opened, by which time the television programme was over and I turned back to Lekki. I went straight to my office, combing my library for any law, gazette or some piece of legislation authorising compulsory sit at home for the observance of environmental sanitation or which sanctioned the arrest of any citizen for alleged violation of the policy. I discovered that it was a programme imposed by the Buhari/Idiagbon military regime, which many civilian administrations carried over.

But times had changed, in Lagos State in particular, as it had created and empowered the Lagos State Waste Management Authority, to be in charge of sanitation and to take care of wastes in all parts of the state. Residents were required to pay a token for this, which I had been paying faithfully. I, therefore, headed to the Federal High Court for a determination of whether I could be arrested by the police for the enforcement of a non-existent law. The court wasted no time in agreeing with me that it was improper to force citizens to stay indoors for environmental sanitation.

I did not know the judge who decided the case and I didn’t have to know him. Sufficient that Hon Justice Idris (as he then was) was able to read through the submissions made before him and he took a courageous decision to uphold the rule of law. And there are thousands of such judges out there all over Nigeria, diligently pursuing the course of justice according to law and according to their conscience. They should be the focus of our attention and protection, before they become endangered.

Adegboruwa is a Senior Advocate of Nigeria.